QBone Part 6: Card Handles 2

Good news! The final components for QBones are finally here. We expect to open the store to sales this week. Check back daily to see the annoucement!

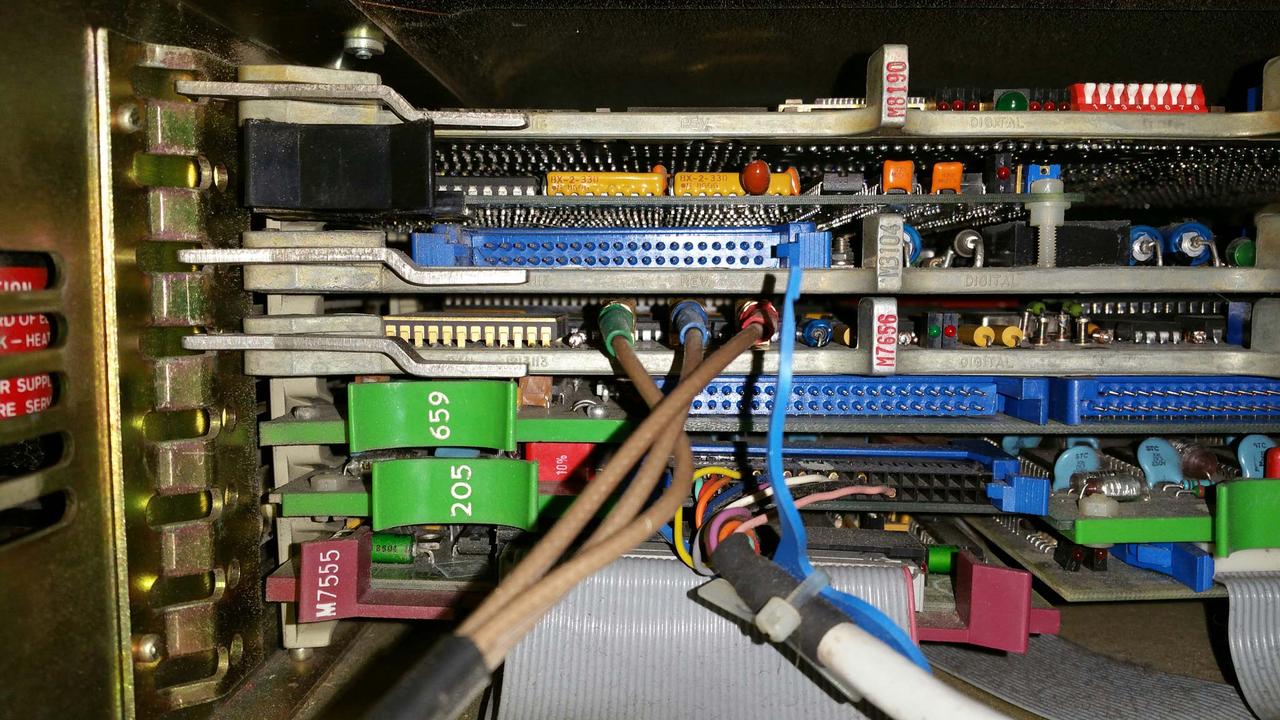

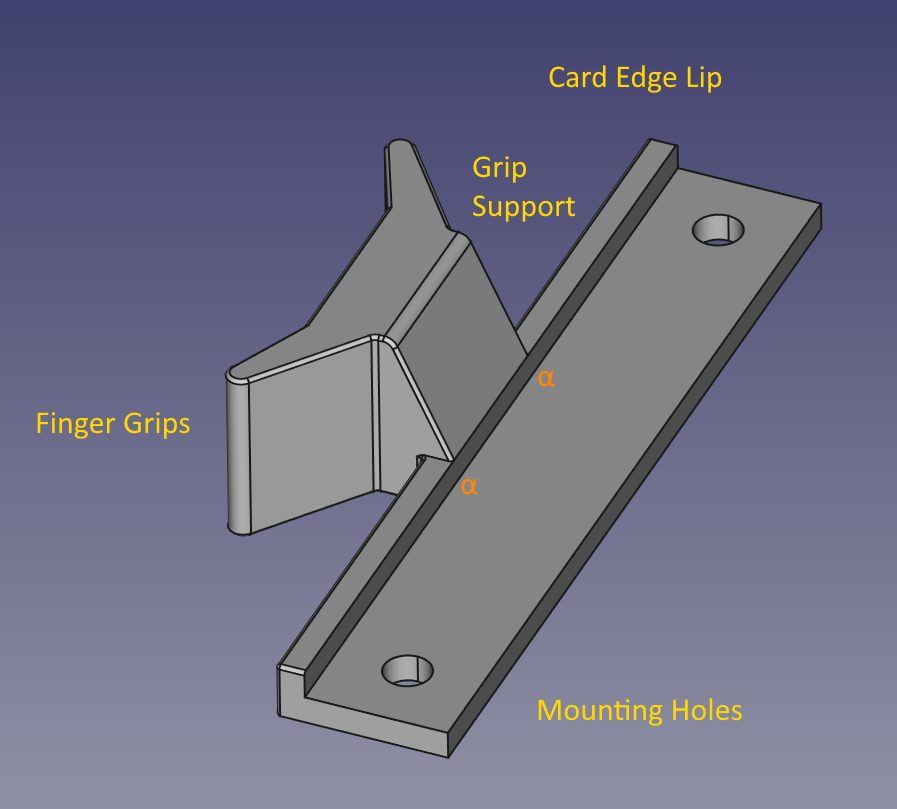

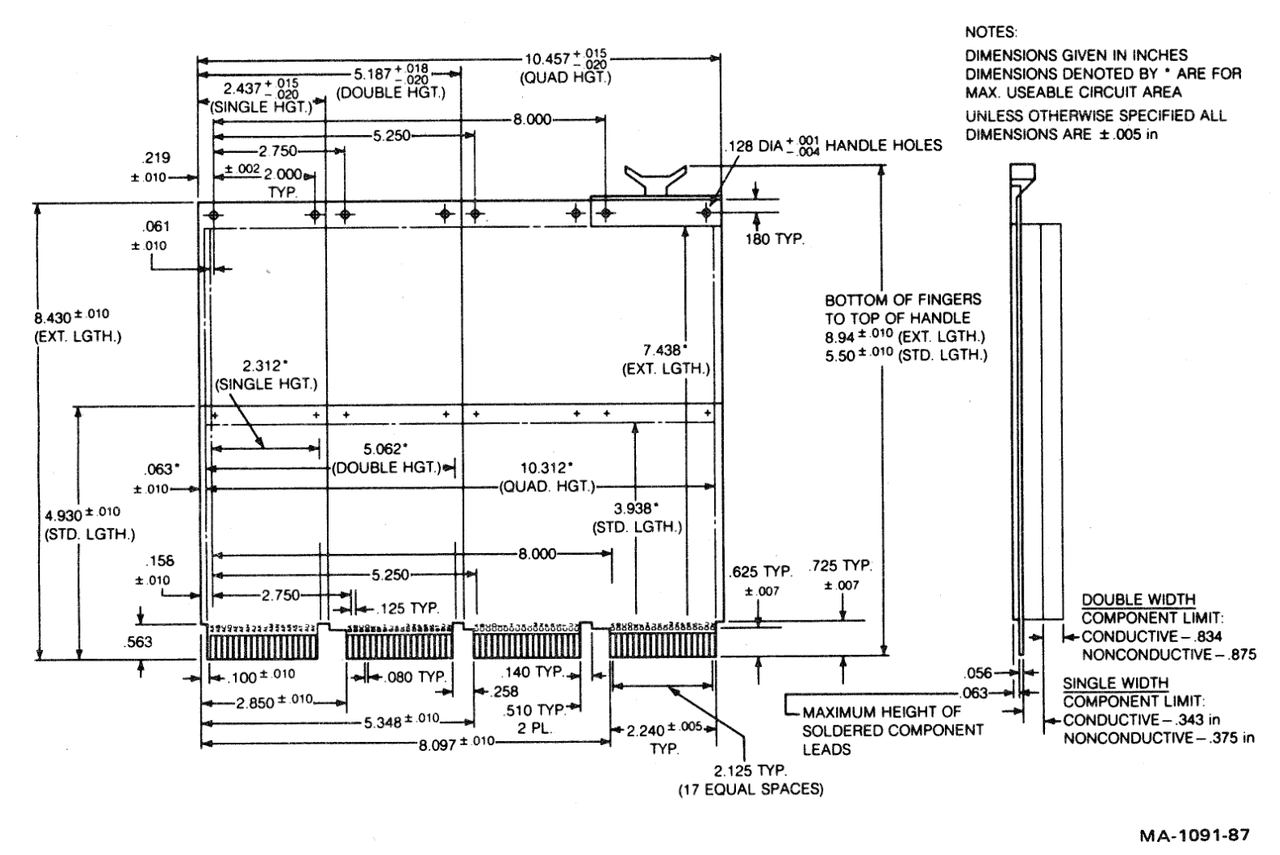

In our last blog post, Chris described the mechanical design of the new QBone card handles in great detail.

While the results on our corporate Prusa i3 MK3S+ are good, I wanted to get as close as possible to a classic, injection-molded handle. But printing with FDM/FFF, even with a small nozzle and a low layer height, still results in visible layer lines fron the front. The PETG we must use for the handles can't be smoothed chemically, and hand-sanding is too time-consuming for mass production.

I decided to try SLA printing. The latest generation of low-cost, UV LED & monochrome LCD resin printers are both affordable and easy to use. In some ways, they're even simpler than filament printers. The operator fills a small vat with liquid plastic resin. Layer by layer, the printer draws each pattern on the LCD screen. UV lighting from underneath the screen is masked by the artwork, curing the resin in the tank in the right pattern and fusing it to the previous layer. The print is suspended upside-down from the print platform, and gradually "pulled" out of the vat over time:

Once the print drips dry, the operator washes the print in isopropyl alcohol and/or soapy water to remove excess liquid resin, removes any mechanical supports used to hold the print to the build plate with flush cutters, and completes a final UV cure of the model. The print can then be painted or topcoated as desired.

The advantages of resin printing are numerous. Our printer sports a 50 micron xy resolution, and layer heights as low as 30 microns. With a variety of resins to work with, the finished product can be quite detailed. But while researching handle manufacturing over the past six months, I encountered two major hurdles with resin printed QBone handles: print quality, and strength.

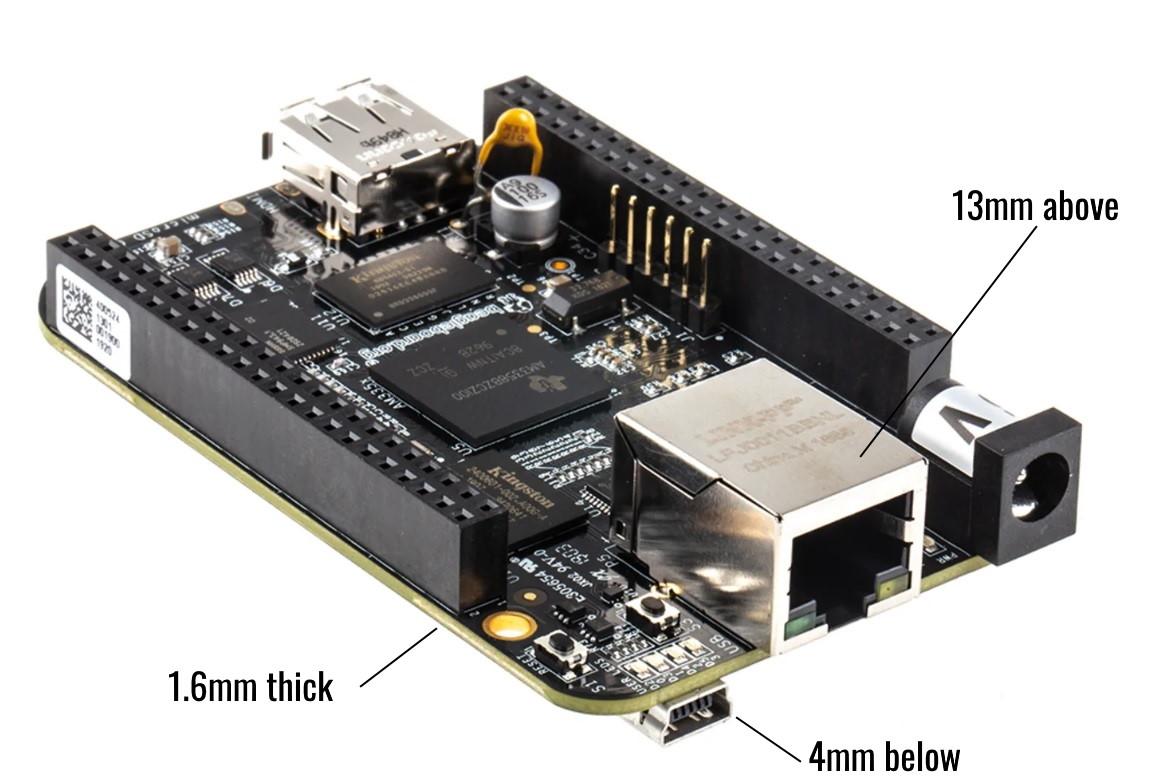

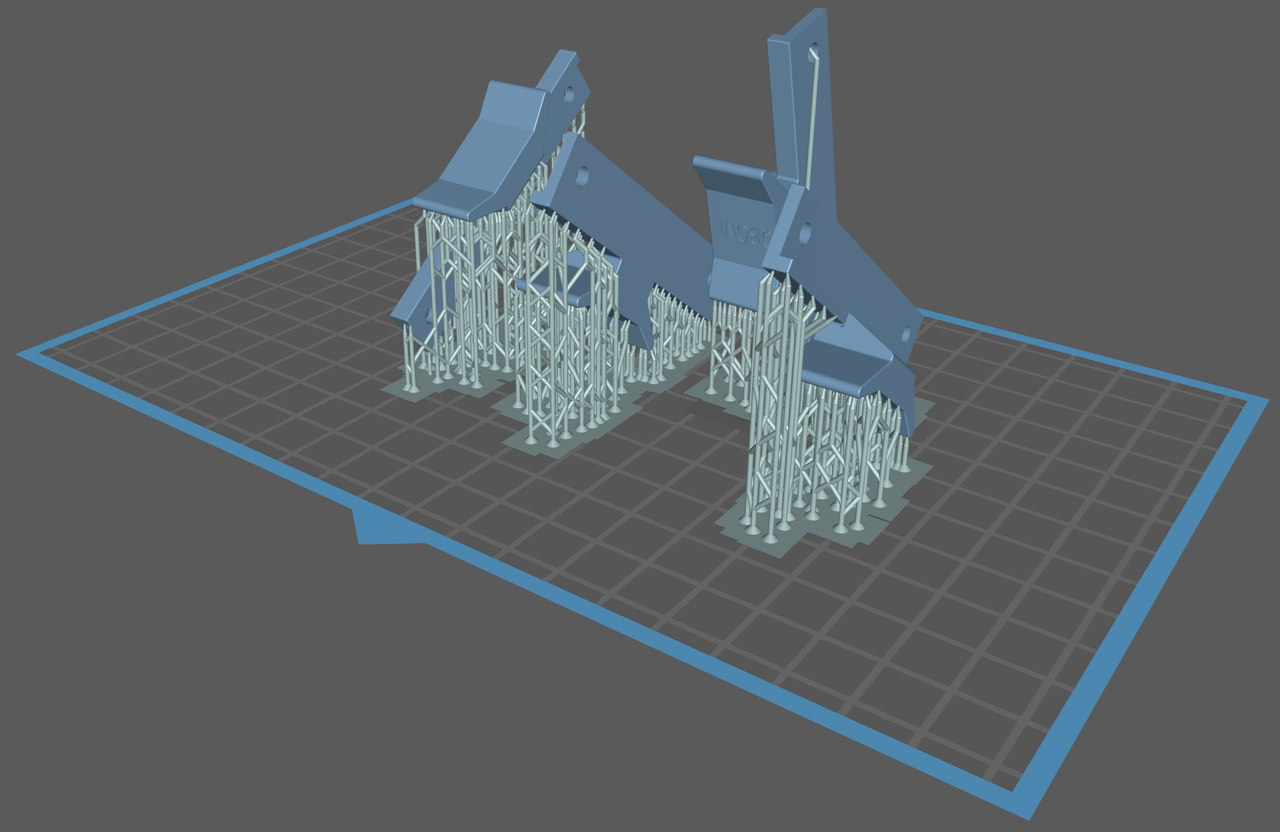

While resin prints produce gorgeous miniatures and artworks, so-called "functional prints" can be difficult to orient for good print results. After a lot of testing, it turned out that orienting the handle nearly vertically produced the best results, with the fewest induced print defects. This is actually great news, because it means we can print more handles at once, increasing throughput.

We tried many, many orientations. The nearly vertical handle towards the back provides the best print.

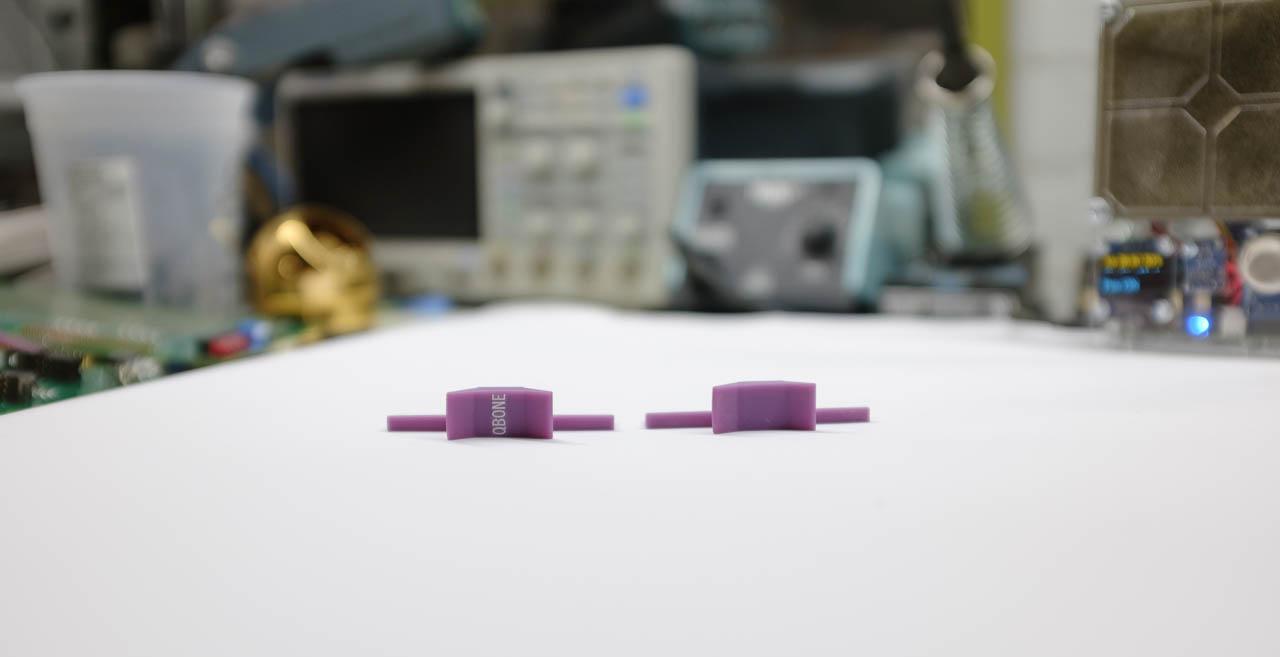

The second issue was resin strength. Resin prints are notorious for being very brittle. Certain resins we tried, including the low-odor, water-washable ones, were especially bad, with prints shattering if dropped onto the floor from waist-height. Thankfully, engineering resins are now available that can produce strong and flexible prints. We use a careful mixture of "ABS-like" resin and a flexible resin, along with a custom pigment mixture, to produce a print with the strength needed, and just enough flex not to break under repeated stress. While these handles are no longer brittle, we still don't recommend dropping a QBone on the floor!

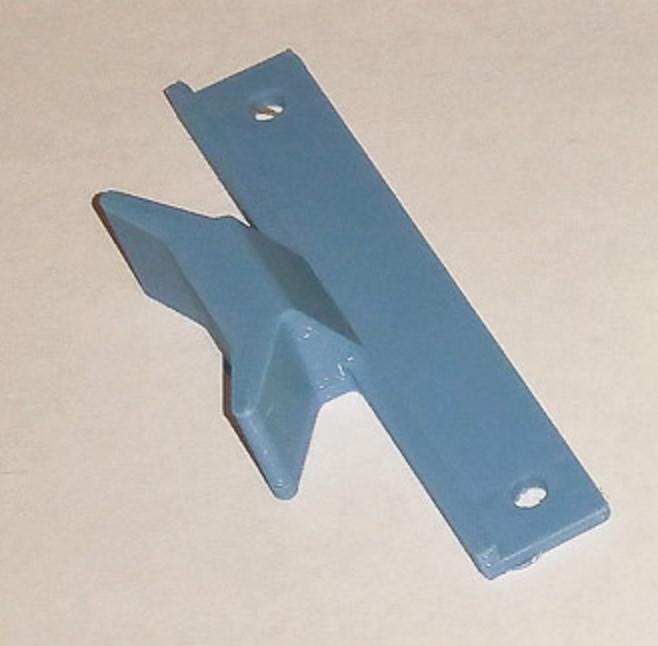

The results speak for themselves:

While QBones will ship with the FFF/FDM handles described last time, these gorgeous resin handles will be available in a few select colours as an upgrade to any QBone order.

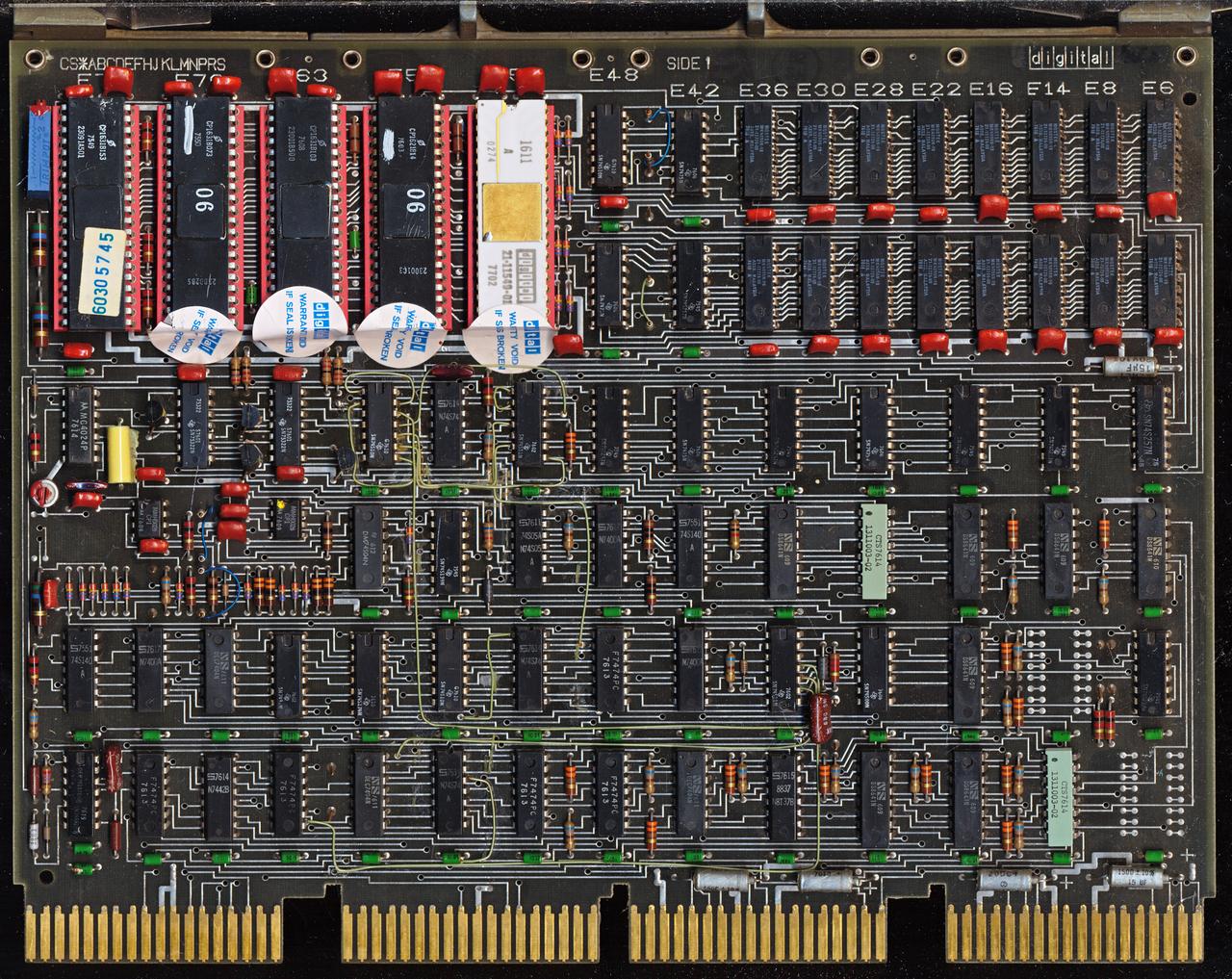

Next time: Going for the Gold.